Deep Coded Wavefront Sensing: Bridging the Simulation-Experiment Gap

Published in NeurIPS 2025 Workshop Learning to Sense (Proceedings Track), 2025

Recommended citation: S. M. Kazim, P. Müller, and I. Ihrke, "Deep Coded Wavefront Sensing: Bridging the Simulation-Experiment Gap," NeurIPS 2025 Workshop Learning to Sense, Sep. 2025 https://openreview.net/pdf?id=4dQlpj6LHc

Abstract – Coded wavefront sensing (CWFS) is a recent computational quantitative phase imaging technique that enables one-shot phase retrieval of biological and other phase specimens. CWFS is readily integrable with standard laboratory microscopes and does not require specialized labor for its usage. The CWFS phase retrieval method is inspired by optical flow, but uses conventional optimization techniques. A main reason for this is the lack of publicly available datasets for CWFS, which prevents researchers from using deep neural networks in CWFS. In this paper, we present a forward model that utilizes wave optics to generate SynthBeads: a CWFS dataset obtained by modeling the complete experimental setup, including wave propagation through refractive index (RI) volumes of spherical microbeads, a standard microscope, and the phase mask, which is a key component of CWFS, with high fidelity. We show that our forward model enables deep CWFS, where pre-trained optical flow networks finetuned on SynthBeads successfully generalize to our SynthCell dataset, experimental microbead measurements, and, remarkably, complex biological specimens, providing quantitative phase estimates and thereby bridging the simulation-experiment gap.

Deep Coded Wavefront Sensing

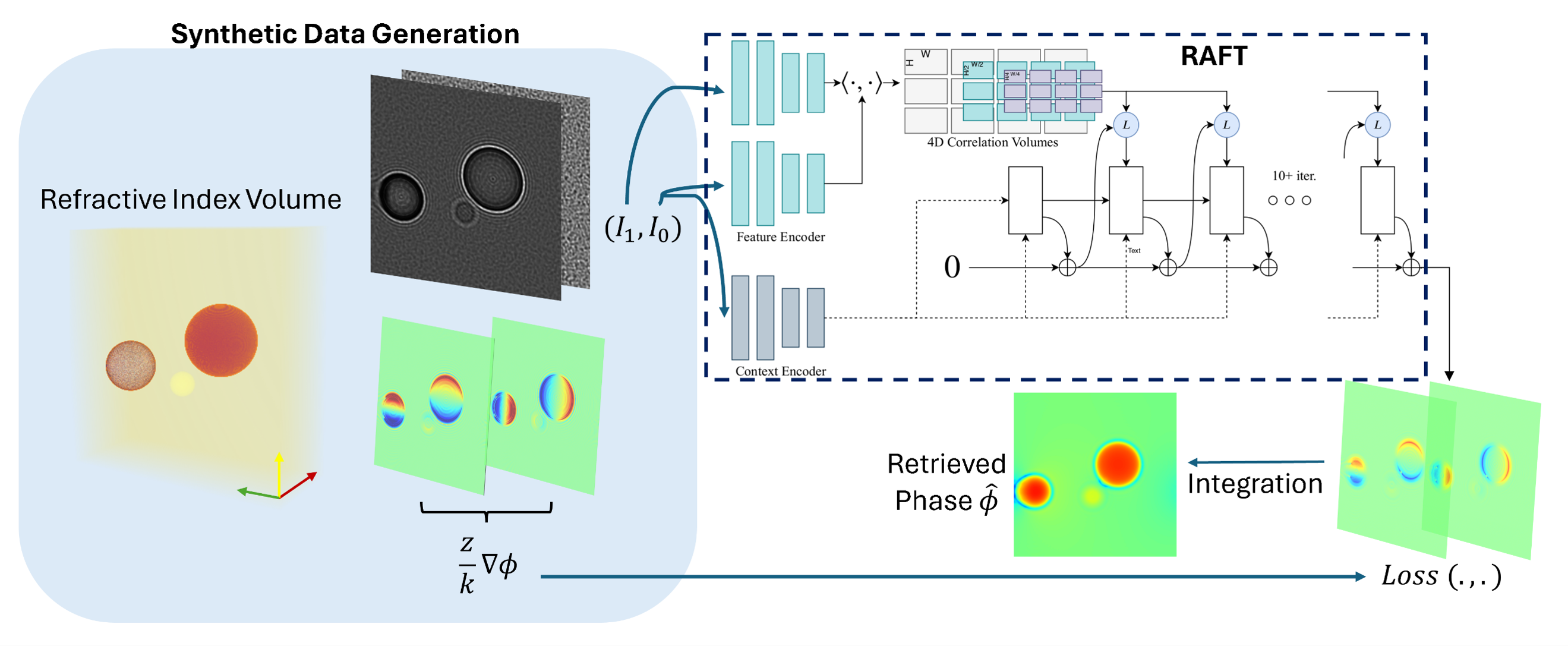

Coded wavefront sensing (WFS) relates the gradient of the phase $ \nabla \phi $ at one plane (the phase mask) to the flow of pixels in another (the image plane), a distance z away.

\(I_1 (r) = I_0 (r + \frac{z}{k} \nabla\phi)\).

The purely optical flow relationship is only partially true in Coded WFS microscopy applications. The propagation of the wavefront by a distance z introduces amplitude variations as well as other features such as diffraction, which are inherent to microscopy. We propose leveraging pretrained optical flow networks by finetuning them with Coded WFS data, one that includes speckles, diffraction, and other microscopy features, so that the networks learn the mapping in the presence of these features, as shown below.

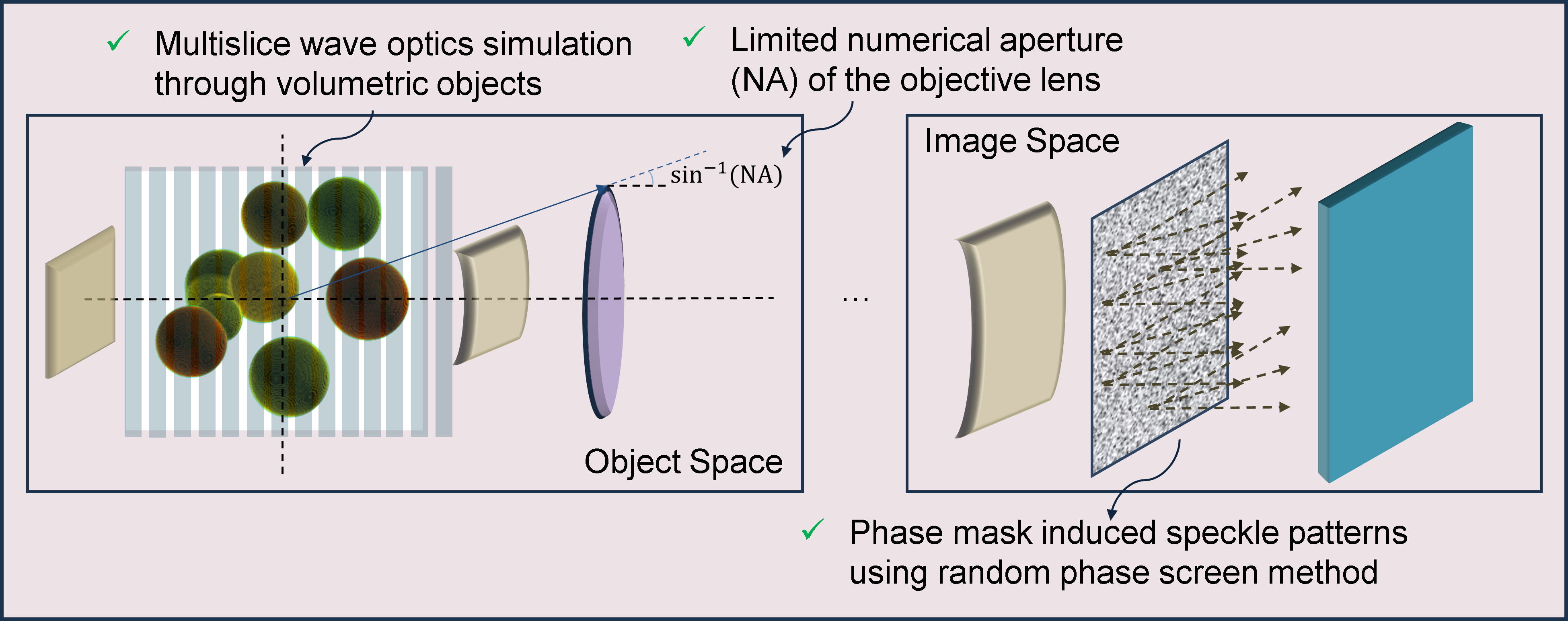

Forward Model Simulation

The entire coded WFS pipeline is accurately simulated using wave optical techniques. Our forward modeling maps the volumetric specimen in the object space to the image plane with high fidelity. The two major components include the microscope, mainly its NA (low pass filtering) and magnification, and the phase mask, which is responsible for the speckle pattern and the primary reason an ordinary camera is converted into an optical flow-based phase retrieval device.

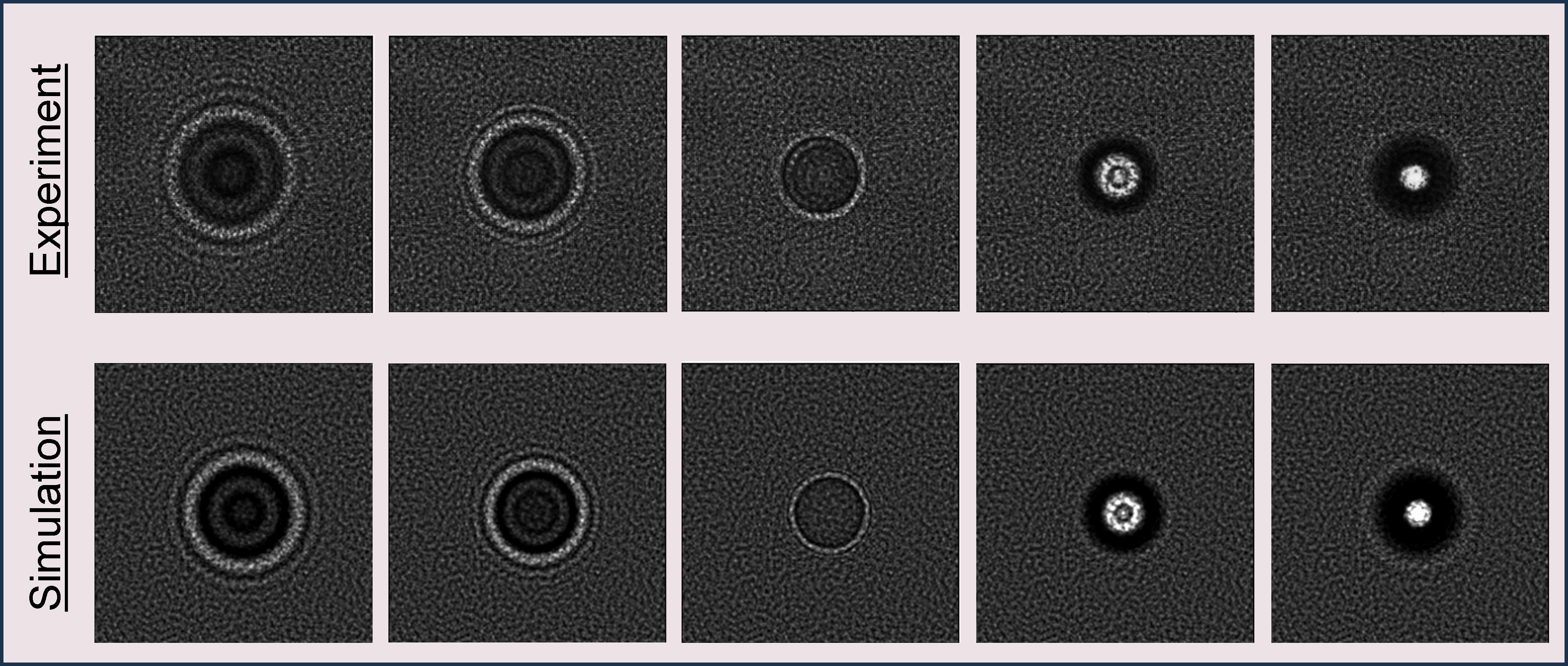

We restrict our volumetric specimens to randomized configurations of spherical objects. By randomly sampling the number of spheres, their radii, positions, refractive indices, and phase mask features (height and smoothing), we ensure that the network does not overfit to specific distributions of objects and remains agnostic to phase mask distributions. Additionally, spheres can be simulated very accurately (and quickly) as shown below, and in the coded WFS setting, where the main features in image space are speckles, we believe the finetuned networks will generalize to non-spherical objects as well.

SynthBeads and TestSynthCells: First Machine Learning Datasets for Coded Wavefront Sensing

Through our accurate wave-optical modeling, we enable Deep Coded WFS (DC-WFS) by producing realistic, synthetic datasets. Optical flow networks can be trained on this dataset. We show in the next section that finetuning on SynthBeads removes the domain gap, such that finetuned networks can provide estimates on measurement data without performance degradation, which occurs when networks trained on synthetic data perform poorly on real data due to simplistic synthetic data not accounting for real features.

Additionally, we propose another dataset, SynthTestCells, which is exclusively a test set. The test set is created by retrieving the phase of a HEK cell in different orientations using DHM, fitting a large number of Zernike polynomials onto these phases, and then statistically sampling these Zernike coefficients, whilst increasing the variance manually to improve diversity of output. Testing on this synthetic biological test set allows us to quantify the performance of the finetuned network on complex, microscopy data.

Results on Synthetic and Real Data

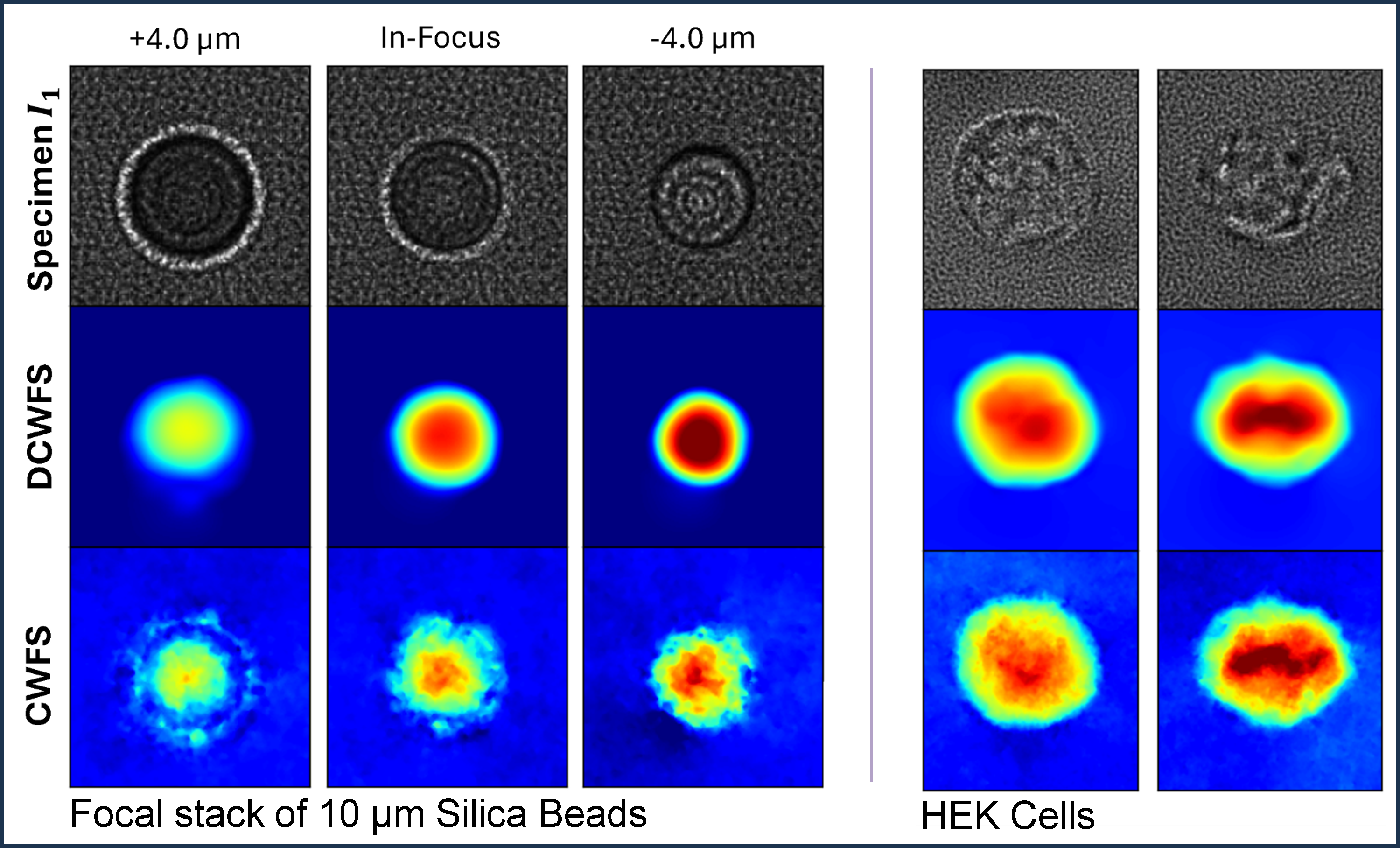

We show two sets of results in the following. Firstly, we show the performance of the finetuned networks on synthetic data. We compare the performance of the network finetuned on SynthBeads, named DCWFS, with the performance of the pretrained network and the traditional ADMM-based method, named CWFS. On the test split of SynthBeads, DC-WFS outperforms other methods, while on SynthTestCells, CWFS edges out our method. The pretrained network, without finetuning on SynthBeads, fails to estimate and produces estimates with large errors (not shown below, table in the article).

Secondly, we compare the performance of real measured data. Here, we do not possess the ground truth, so the comparison is largely qualitative. We measure microbeads and real HEK cells using CWFS hardware. We retrieve the phases with the traditional method and DC-WFS. For the microbeads, as it is a simple spherical object with a constant refractive index, we can accurately estimate that the OPD is smooth and the maximum OPD is the geometric delay. Given our expectations, we see that DC-WFS outperforms CWFS, indicating no domain gap between simulated and real data. For the HEK cell results, we can see that DC-WFS, as with SynthTestCells, generalizes to complex unseen biological data. However, the outputs of DC-WFS may be smooth, as is evidenced by the SynthTestCells, where certain details in the interior are merged, reflecting a low-resolution estimate.